The beautiful Brecon Beacons National Park covers over 500 square miles on the border between Mid and South Wales. We drove up from Hay-on-Wye into a mysterious area that contains some of the highest peaks in Wales, includes a UNESCO Global Geopark and is an International Dark Sky Reserve. And soon the Park will reclaim its’ original Welsh name and become Bannau Brycheiniog National Park. We encountered a way of preserving land into a National Park that was very different from American National Parks. In the US, we tend to value wilderness and little development in our parks. Here, local agriculture is preserved along with the stunning views and remarkable landscapes. Roman forts and Celtic settlements were part of the park along with the rich natural beauty and remote rugged mountains of the area.

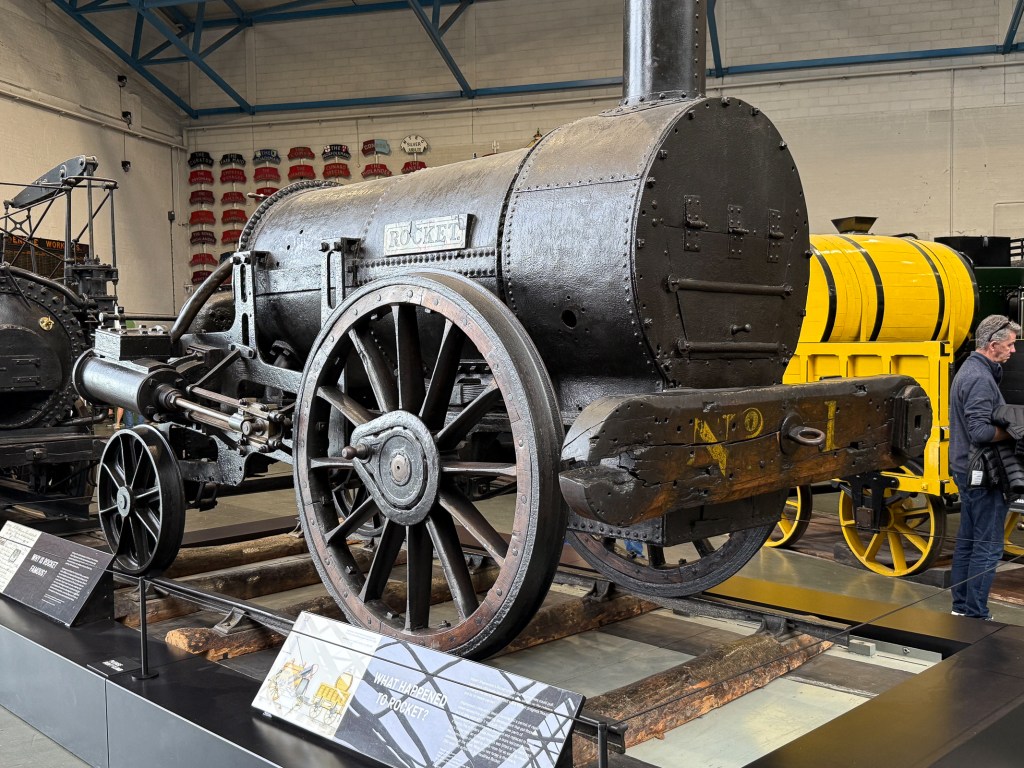

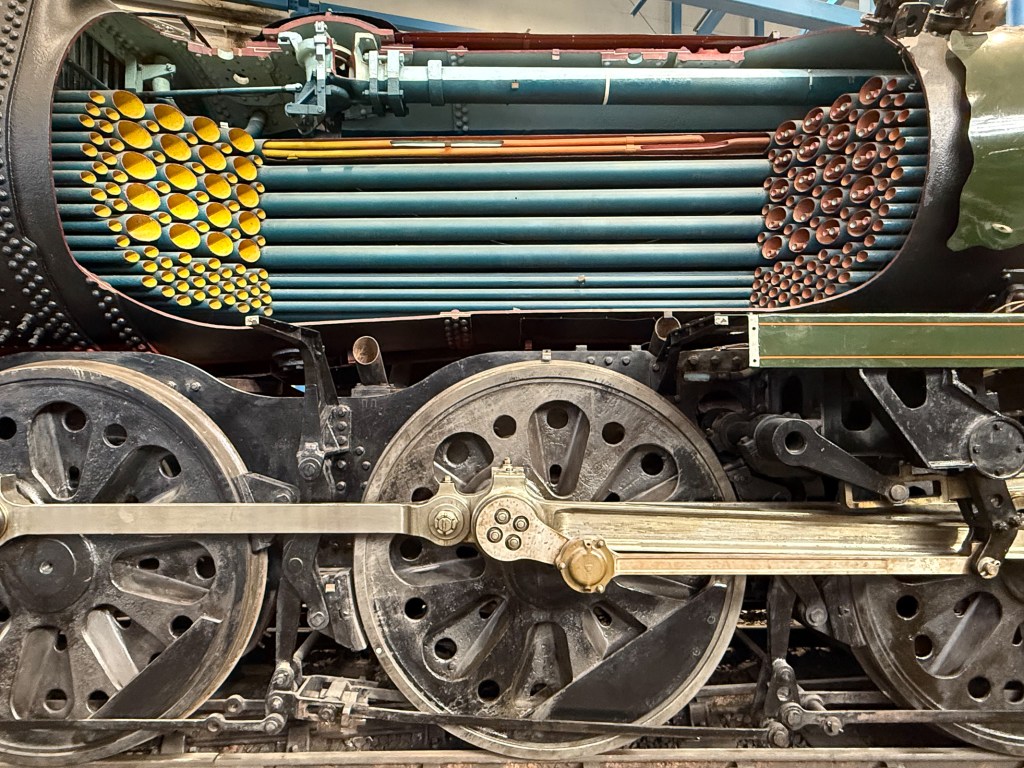

Merthyr Tydfil took its name from a martyred daughter of a Christian King in 480 CE. It is noted for its industrial past and was known as the “Iron Capital of the World” in the early 19th century. The world’s first steam-powered railway journey happened in Merthyr in 1804 appropriately from an ironwork to a canal. By the mid-1850s, Wales became the world’s first industrialized nation, as more people were employed in industry than agriculture, with Merthyr the biggest town in Wales at the time. The Donetsk region in Ukraine was originally developed as a mining and iron work area by a man from Merthyr in 1870. By the early 20th century Merthyr began long decline as mining and smelting jobs left the area culminating with a TV report listing Merthyr as one of the worst places to live in the UK.

Our interest in this post-industrial area was, of course, the story of its library. The new library was built on land donated by the local ironworks in Dowlais neighborhood and opened “with a flourish and a key made of gold” in 1907 with funding by Andrew Carnegie. The neighborhood today was a little rough, and the library reflected the faded beauty of its former glory days. Inside were many paintings of the area’s industrial past. Some romanticized the history, and others suggested a worker’s hellhole. One writer in 1850 while visiting Merthyr observed “It is like a vision of Hell, and will never leave me, that of those poor creatures broiling, all in sweat and dirt, amid their furnaces, pits, and rolling mills.” We later learned that in the epic series The Lord of the Rings, J.R.R. Tolkien, who lived in Wales, used the image of industrial Merthyr for the place he called Mordor. Even the names are similar. I had a fascinating conversation with a local man who was a socialist and very aware of the struggles of the workers in Merthyr. He suggested that I learn more by reading a book called Merthyr Rising which describes one of the world’s first industrial worker’s resistance to the inhumane working conditions of the newly emerging Industrial Revolution. He was a delight, and I will certainly read that book when we get back. We finished up the day photographing another Carnegie funded library in the struggling former-industrial town of Treharris. This one was undergoing a beautiful restoration and will reopen soon.

The Welsh capital of Cardiff was a delight. It feels like a very comfortable place to live, and we were impressed by the sparkling culture and cuisine. But like in San Francisco, the booming economy of the city is also leading to increasing income inequality and an unaffordable cost of living for many people here. Like the province of Quebec in Canada, Wales is proudly and thoroughly bi-lingual.

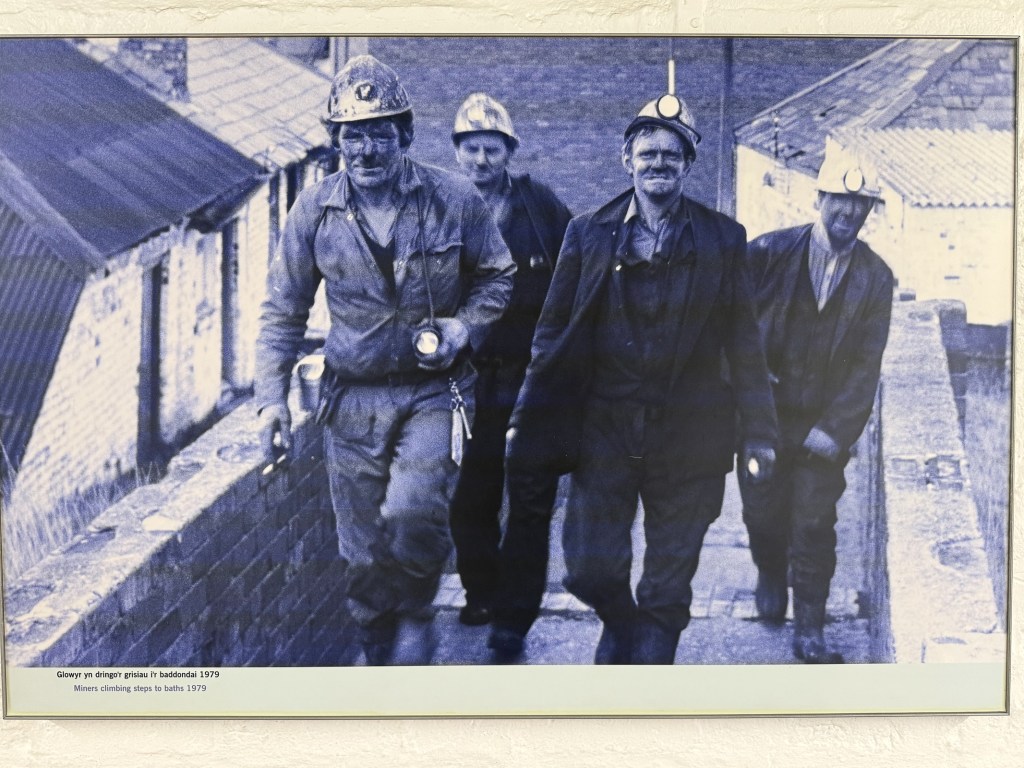

The next day we went to the Big Pit National Coal Museum. Set in the Blaenafon Industrial Landscape, it is a UNESCO World Heritage Site and is considered one of the best mining museums in the world. It is one of the oldest and most important of all the large-scale industrial coal mining developments in South Wales and one of the last working coal mines in the area. The history of this place was hard and came alive through the wonderful use of historical photographs posted throughout the tour. We did the hour-long underground tour with an ex-miner and a group of other interested folks. There is no better way of understanding the claustrophobic world of a miner than being in a mine when they turn out lights and you stare into blackness. This well-formed museum touched me with its good use of history, photography, illustrations, installations and art. Plus, I will never forget the visceral tour of the mine.

Returning to Cardiff for our final night, we dined at the Botanist. There are a series of these throughout the UK and the last one we went to was in Birmingham, England. It is loosely based on a theme of early 19th century woman’s illustrations for botanical texts. The food was delicious and both places were fascinating. The next morning, we bought some of the famous Welsh cakes that were originally the food for miners but now are slightly sweet delights needed to continue a long library road trip.

Next stop: Bath and beyond…